Fallen Angel! The political cartoons of Jimmy Friell

Gabriel: One of the archangels who appears in the Jewish Christian and Muslim belief-systems. Christians hold that Gabriel was the angel of Annunciation… it is he who is to blow the trumpet on judgement day.

Among the London newspaper cartoonists of the late 1930s, only David Low at Beaverbrook’s Evening Standard and Gabriel at the Daily Worker provided any sustained opposition to the Government at home and the Fascists abroad. Gabriel (James “Jimmy” Friell) and Low saw the sell-out of Central Europe coming early on. Their warnings went largely ignored among the ruling elite, except when they irritated Hitler and Mussolini or Franco. To the British rulers of the late 1930s, dissident Liberal cartoonists such as Low and a radical one such as Gabriel were little more than amusing irritants, unless their images and ideas influenced events at home and especially abroad.

How did a blonde Irish-Catholic Glaswegian come to be a radical cartoonist during the shirt lived heyday of the Daily Worker? His father was a straight man in a comic duo in the Scottish music halls. The year Friell was born, 1912, his father’s comic partner quit. “My old man never did more than a few continuous months’ work in my whole life,” he told me with a laugh. “I once had to fill out a political questionnaire, which asked are you a member of the upper class, middle class or working class? I crossed ‘em all out and said ‘unemployed class’.”

At 14, Friell took a dead-end job as a solicitor’s office boy. He escaped through cartooning. By his eighteenth birthday he was making enough money as a free-lance humorous artist and journalist for Scottish newspapers to rent a studio. In 1930, of his family of nine only he and his eldest sister Cissie were employed. They existed on the dole, plus what the working two could bring in. Given his talents and intellectual interests “I thought I had to get to London. You have to realise there was desperate deprivation in Glasgow. I also wanted to be in the middle of things and I had literary inclinations.” His route to London ran through the Glasgow School of Art and Kodak. The school recommended him to Kodak as a commercial artist. Eighteen months later, Kodak sent him to London. By then he was earning about twice the wages of an ordinary employed worker. At a political rally some years later someone asked him “What made you first want to become a cartoonist?” His answer “Money.”

The increasingly desperate mid-1930s, when British leaders neglected their people, their defences and their position in Europe stimulated and appalled Friell. He remained scornful of the Establishment and their publicised foibles. In 1986, Friell commented bitterly “I don’t know why there wasn’t a bloody revolution.”

In 1935, he sent some satirical political cartoons to the Daily Worker, guessing correctly that it was the only newspaper radical enough to print them. The Daily Worker’s staff liked his cartoons but couldn’t pay him. Friell told them to use them anyway. A few months later the paper offered him a job as their regular cartoonist, and he joined them early in March 1936. By then, the Daily Worker’s staff had transformed a rather pathetic propaganda organ, begun in 1930 by the Communist Party of Great Britain, into a fully professional newspaper. Its appearance and contents were as up-to-date as any mainstream Fleet Street paper. The addition of Gabriel’s cartoons gave its leader/editorial page a new cutting edge, as did his other work on the paper. Bill Rust, one of the founders and editors, noted Friell’s arrival:

Gabriel first appeared on the scene in February 1936. In him was immediately recognised an artist with a sure political understanding. Both his artistic and political ‘line’ were just what we were waiting for! Apart from being a cartoonist, Gabriel is also a writer and critic of considerable talent. Jimmy Friell chose an appropriate nom de guerre for his Daily Worker cartoons:

In one way or another then it looked like the last trumpet was being sounded for existing society, so I took the pen name of Gabriel, the Archangel and settled down to helping the process along. My value lay in supplying the humour that the paper rather desperately needed.

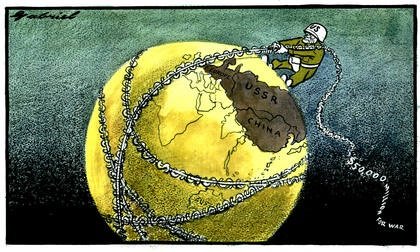

His cartoons mordantly illustrate WH Auden’s epitaph for the 1930s. “The clever hopes expire, of a low dishonest decade.” His subjects ranged from the Hunger Marchers, the debilitating unemployment and the meagre dole, the state of race relations, the thuggery of the British Union of Fascists to the increasing threat to peace from the Fascists abroad.

Gabriel was particularly witty at using British national symbols to deride the systematic news management of the Government. On the threat of war from the Japanese and the Fascists, he was strikingly prescient. His depictions of Franco, Mussolini and Hitler are only exceeded in their bite by his series of attacks on the tragically misguided Neville Chamberlain. Perhaps his most memorable symbol was the Axis horse (or mule?) – a centaur with Hitler’s head, and Mussolini as its hind end.

Before the war Friell and the Daily Worker were almost entirely in agreement over whom to attack and whom to support. “I never produced a cartoon in consultation with anybody.” At the Daily Worker Gabriel asserted, “I never found any trouble. Apart from ‘technicalities’... was it Trotsky or was it Stalin, was it this or that...my views coincided with them. I never made any attacks on the ultra-left...it was for me straightforward.”

The announcement of the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact “...was a shock to everybody”, he affirmed. “Nobody like it, but if you examined it, you could see why it was necessary to Russia.” Subsequent public explanations masked a fundamental split in the British Party’s leadership. Friell and the rest of the Daily Worker staff were well aware of the split. “Oh Christ, we did [know], ‘cause we didn’t have a bloody line about it.” Friell pointed out that the Party and the Daily Worker never took any official line against the war, or a CP member joining the forces, and to his knowledge, no party member was a conscientious objector.

Friell was called up in September 1940. Posted to an ‘ack ack’ battery, he sent drawings when he could, to the Daily Worker. Even the British Army eventually used him for his manifest skills and talents. In 1944 he was appointed art editor of Soldier, and followed the Army into Europe. He was discharged in January 1946. Friell was profoundly affected by the depression, and by his five and one-half years in the Army. By dint of concentrated effort, he had escaped “annihilation by unemployment” and found a calling at the Daily Worker in the late 1930s. His ‘war stories’ are tinged with a certain amount of nostalgia. Many soldiers he knew were convinced the Tories and the Royal family were ‘washed up’. Faith in change, he told me, kept you going during the war, when ‘Civvy Street’ seemed a mirage. To add to his mood, his pre-war original drawings were all destroyed in the Blitz.

Old comrades and the Daily Worker’s editor persuaded him to return to the newspaper. For the next 10 years he prodded the Labour Government about delaying the promised new utopia and the end of the empire, and criticised the Cold War.

In November 1956, disillusioned by Stalin and the British Party’s authoritarianism, he walked out over the hypocritical stance the newspaper took over the Russian invasion of Hungary. ‘I couldn't conceive carrying on cartooning about the evils of capitalism and imperialism,’ Friell later wrote, ‘and ignoring the acknowledged evils of Russian Communism.’

After six months unemployment, Jimmy Friell accepted Lord Beaverbrook’s offer, first extended in the late 1930s, to cartoon under his own name for the Evening Standard with “complete political freedom” despite the fact that there were a number of top executives at Express Newspapers concerned about Friell’s ‘extreme’ left-wing views. When he left the Daily Worker, he told his former colleagues he would never use Gabriel in another paper. He was, after all, starting another life. Friell spent six years at the Evening Standard, only to be pushed aside, ironically by the emotionally radical Vicky.

After two years with no income at all, “not a sausage!” he found work in television and in magazines as a joke cartoonist. No newspaper would knowingly hire him to do political cartoons. At that time only Beaverbrook had any coherent notion of how to use political cartoonists. Most editors wanted a gagster, and they were not about to hire a satirist who contradicted their or their readers’ views. Low, Vicky and their principal patron, admirer and victim, Lord Beaverbrook, died in the 1960s. Since then one of Britain’s most witty and perceptive radical cartoonists has not been able to practise his craft.

For 20 years Gabriel blazoned the anti-Fascist cause and radical socialism at the Daily Worker. His cartoons – caustic, heartfelt, often funny, full of stark contrasts, are a reminder of attitudes and conditions during the late 1930s – what Alfred Hitchcock labelled “the corrupt and stupid years”. Gabriel’s career and his cartoons also provide a window on the British Communist Party during the desperate era of the Popular front, the Spanish civil war, the Stalinist Purges, the tragic appeasement of Hitler, the Party’s discord over the Nazi-Soviet pact, the “People’s War”, the Cold War, and its post-war disintegration.

Jimmy Friell still published joke cartoons into his mid seventees, but regretted not having the opportunity to satirise Thatcher, Reagan, Gorbachov and Bush. In August 1989 he remarked: “Not to be able to say anything about the political situation in the last ten years is purgatory”. Friell died at his home in Ealing, West London, on 4 February 1997.

In association with the British Cartoon Archive, an exhibition of Jimmy Friell’s original cartoons was held at the Political Cartoon Gallery in March 2007.

View Account

View Account