Sir David Low on Sir Winston Churchill

by Dr Timothy S. Benson

The proprietor of the Evening Standard, Lord Beaverbrook, said of David Low's cartoons that as 'comments on contemporary events they stand triumphantly the test of time'. Who then better to capture with humour Sir Winston Churchill's illustrious career as politician and war leader than his contemporary Sir David Low. Few other cartoonists drew Churchill over such a long and momentous period. From 1919 to 1962, working for the Star, Evening Standard, Daily Herald, and the Manchester Guardian, Low drew with what A.J.P. Taylor called a 'savage realism' to portray Churchill in whatever guise he saw appropriate.

Low had a genius for depicting those that displeased him as both foolish and ridiculous. This naturally meant that the eccentric Churchill, with his egocentric personality along with his capacity for political misjudgement, offered a welcome target. From his futile attempts to persuade Lloyd George to intervene in the Russia Civil War in 1919 through to his retirement, Churchill was taken to task by the cartoonist at every available opportunity.

Yet while Low may not have cared for Churchill's demeanour or his politics, he was prepared to champion his cause when justified. He was totally in sympathy with Churchill's warnings over Hitler's intentions in the late 1930s. When war eventually broke out in September 1939, Low's cartoons portrayed Churchill as the only man capable of offering Britain the stoic leadership that it needed. On him becoming Prime Minister, it was Low's cartoon 'All behind you Winston' that captured the public mood of Churchill's determined leadership. Throughout the whole of the Second World War Low continually upheld Churchill's role as war leader without once denigrating or ridiculing him.

Low's astute understanding of character and personality made him quickly appreciate that Churchill, despite his flaws, was a unique figure in British politics. He recognised the man's genius if at times this led him to draw him as a restless and often misguided figure within the British establishment. From Low's own political and social standpoint, he saw fit to deride Churchill. Unlike the many biographers who have since been happy to reproach or praise Churchill in the light of history, Low never had the benefit or luxury of hindsight. His cartoons show us a contemporary view that has stood the test of time.

Low's draughtsmanship and 'high political intelligence' as Michael Foot, his former editor at the Evening Standard, called it were legendary, but his foresight set him apart from other cartoonists. For example, he quickly foresaw that the cost of war reparations to the vanquished German people would lead to a future war, as Germany would eventually demand revenge for such humiliating treatment. He foresaw the futility of Churchill's anti-Bolshevik crusade in 1919, and in 1930 foresaw Ramsay MacDonald's desertion from the Labour Party to form a National Government. Most impressively of all, he prophesied, as early on as 1931, the dangers to European stability from Adolph Hitler.

From a social standpoint Low and Churchill had little in common. The aristocratic Churchill was born at Blenheim Palace, grandson to the Duke of Marlborough, and son of an ex-Tory Cabinet Minister. Low on the other hand was a native New Zealander whose grandfather, a marine engineer, had emigrated there from the Scottish highlands. Low's upbringing in the egalitarian and liberal environment of New Zealand and Australia led him to develop a distaste for the snobbery and inequalities which he found upon his arrival in England.

In October 1919, David Low left Australia and the Sydney Bulletin where he had earned a reputation as one of Australia's leading cartoonists. On Arnold Bennett's recommendation the Star, a London evening newspaper owned by the Cadbury family, had offered Low the opportunity of becoming their new cartoonist. This he gratefully accepted. Churchill was Lloyd George's Secretary of State for War at this time, having been appointed in January 1919 with the responsibility for quickly demobilising British troops after the ending of the First World War. His reputation as a politician had at this time still not recovered from his wartime role as First Lord of the Admiralty. It was common for his public meetings to be still interrupted by cries of "What about the Dardanelles?" (a reference to the failed landing against Turkey for which Churchill was seen to be responsible.) What is surprising, is that while concentrating on the Allied war effort at the Sydney Bulletin, Low had kept an open mind over Churchill's contribution to the disastrous Dardanelles campaign. None of his cartoons during the conflict ever featured or directly attributed blame to Churchill for what in effect became the futile slaughter of many thousands of Australian and New Zealand troops. The British politician that took most of Low's ridicule was the then Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. It was his inability to maximise fully Britain's war effort on the Western Front that had led in no small part, to Churchill's concept of an alternative front against Turkey.

The first time Low met Winston Churchill in person was just after the 1922 General Election. He had been invited by Lloyd George to a dinner at the House of Commons, where he found himself sitting right opposite Churchill. Low having caricatured him for the previous three years from afar, noted that Churchill in the flesh belonged 'to that sandy type which cannot be rendered properly in black lines. His eyes, blue, bulbous and heavy lidded, would be impossible. The best one could do with them would be an approximation. At this time all the political cartoonists were using the approximation worked out by E.T. Reed, the Punch caricaturist who was feeling a bit disgruntled about the plagiarism. 'That fellow.' Reed complained to me about a colleague, 'he's a thief. He stole my Winston's eye."'

Low then recalled how his perception of Churchill since 1919 had differed little from the man he now conversed with at the dinner table:

'I already knew about Churchill. Who hadn't? Born in the inner circle, but combining with that long start exceptional abilities; determined to be a big noise; broke from Tory Party to Liberal Party when young to find opportunity; Sydney Street; the Admiralty; The Man Who Had the Navy Ready... and so on. A democrat? An upholder of democracy? Um-ah-yes... when he was leading it. Impatient with it when he was not. Consequently not naturally a good politician, but astute from experience. As might be expected from his origins and temperament, inwardly contemptuous of the 'common man' when the 'common man' sought to interfere in his (the common man's') own government; but bearing with the need to appear sympathetic and compliant to the popular will. In those days, whenever I heard Churchill's dramatic periods about democracy, I felt inclined to say 'Please define.' His definition, I felt, would be something like 'government of the people, for the people, by benevolent and paternal ruling-class chaps like me.' Remembering him as one of the most energetic miseducators of public opinion in the early nineteen twenties, when his dislike of political onrushes from below took him within hail of fascism, when the rabbits of the T.U.C. were held up as Russian bears and the idea of a Labour Government was alleged to mean the enthronement of Bolshevism at Westminster, I could never accept him as a democrat in the Lincolnian sense. Winston's characteristics were confidence in himself and love of his country. His defence of England was always against threatening foreigners rather than against threatening 'isms or 'ologies, which did not worry him, since he was sure he would eventually turn up leading the winner. A high sense of the dramatic; a talent for self-advertisement; and to cap all, imagination and guts.

Churchill was witty and easy to talk to until I said that the Australians were an independent people who could not be expected to follow Britain without question they were, in the case of new wars, for instance, not to be taken for granted, but would follow their own judgement. His eyes bulged a little, his face seemed to rise and hang in the heavens and he ended the subject with a piece of rhetoric to which there could be no reply. The conversation turned to Art. An enforced political "rest" had turned his interest to a new hobby, painting. His ideas of how I worked were fantastic. He thought I made a drawing in half an hour, and I had some trouble in explaining that it would take longer than that to put the lines down on paper in disorder, without trying to draw at all. But for all that he had a genuine appreciation of quality in caricatural draughtsmanship. He flattered me by recalling some of my old cartoons which I had thought forgotten. Once on another and later occasion he made me blush by advancing across a roomful of people with pencil and paper, ostentatiously pretending to make a sketch of me, till I threatened to make a political speech. For all his playfulness I find that I wrote at the time of these first impressions: 'Churchill is one of the few men I have met who even in the flesh give me the impression of genius. Shaw is another. It is amusing to know that each thinks the other is much overrated.'

Such sentiments meant that Low invariably found in Churchill a worthy target. His attitude towards Empire, the working classes, and his fear of a Labour Government, meant that the cartoonist took full advantage in making him Labour's most valuable propaganda asset. When Churchill began his almost personal campaign against Bolshevism in Russia, demanding a commitment from Lloyd George to send British troops to intervene in support of the Anti-Bolshevik forces, Low continually depicted him as a warmonger and arch reactionary. To the Star readership, Low's cartoons confirmed Churchill as an irresponsible eccentric who could not be trusted. Even Lloyd George who had become increasingly exasperated by Churchill over his zealous pre-occupation over the Bolshevik threat described him as 'the only remaining specimen of a real Tory'.

Low began caricaturing Churchill in a cast-off Napoleonic uniform, embodying his image as an adventurer with an obsession, like that of Napoleon himself, to conquer Russia. This image of a Napoleonic Churchill was also popular amongst contemporary opinion, as most people viewed him at the time as an emblem of concealed reaction. H.G. Wells also had little sympathy for Churchill's view of the new Communist State, and parodied him as Napoleon in his play Men Like Gods.

Churchill, who had a reputation for being unable to manage his own personal finances, was made Chancellor of the Exchequer after the 1924 General Election by the then Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. Low saw that although the appointment was inappropriate, it did offer further scope for amusement especially at Budget time. Churchill did not let him down, his Budget speeches were always hugely entertaining, while his handling of the economy gave the cartoonist a perfect pretext to castigate him.

During the General Strike in 1926 Low and Churchill once again found themselves in opposite camps. Churchill was the leading advocate within the Cabinet of taking on the miners. He denounced the British worker as the 'enemy' and demanded 'unconditional surrender'. To Low fighting seemed Churchill's natural response to any challenge, but unexpectedly he did not feature him in any of his cartoons during the General Strike. Churchill only appeared months later and remarkably as a sympathetic conciliator on behalf of the miners, who had continued to stay out on strike despite the failure of the General Strike (57). Despite this one would have thought that Low's antipathy would have grown because of Churchill's earlier course of action, but surprisingly he declared at the time that:

'Churchill is far and away the best actor, he is now the most striking and drawable personality in British public life. I like drawing Mr Churchill, his face is full of humorous atmosphere.'

Many commentators believe that Churchill grew to loathe Low. There is little substance to this. Churchill, himself an enthusiastic artist, greatly admired Low's draughtsmanship. According to Low, 'Winston is very interested in caricature and will yarn for hours on the technical side of art.' Churchill also acknowledged Low's genius: 'Low is a great master of black and white; he is the Charlie Chaplin of caricature, and tragedy and comedy are the same to him.' In January 1924 Churchill paid what was at the time another striking tribute to Low:

''It was the turn of the Press to satirise the politician at the present moment if they were not satisfied already by the very full indulgence which we daily see in the brilliant cartoons of Low.'

Not surprisingly, Churchill became an avid collector of Low's original drawings in which he appeared. He even on occasions, while Prime Minister, requested Low's originals as presents for foreign emissaries, as in the case of Harry Hopkins who was at the time President Roosevelt's special advisor. Churchill described Hopkins's present as a cartoon of himself with President Roosevelt sitting on a sofa; 'with a scruffy looking Harry in the background'. Finally, as late as the early 1960s, Churchill still admired Low to such an extent that he chose him, above all others, to illustrate the North American serialisation of his memoirs.

Yet there is also no doubt that Churchill disliked Low's politics, his left-wing sympathies and what he often saw as his continual attempts to deride the British Empire. He therefore described him politically as:

'A little pre-war Australian radical. When he was growing to years of discretion, the best way of getting a laugh was to gibe at the established order of things, and especially at the British Empire. To jeer at its fatted soul is the delight of the green-eyed young Antipodean radical.'

According to an interview with Frank Owen in October 1937, Churchill had bitterly attacked Low as a scoundrel, whom he said, 'never drew a single line in praise of England'. There were even times in 1940, when Churchill, under enormous pressure due to Britain's precarious position, believed Low was even a dangerous subversive, doing great harm to the morale of the country. Towards the end of the war, Churchill due to his stronger ties with Beaverbrook, was able to block a cartoon about the situation in Greece. The explanation given to Low was that this was 'in the interests of western democracy'.

Though Churchill was usually happy to be caricatured by Low, he sometimes became very concerned when his son Randolph, whose insolent manner made him an easy target for the media, was also derided. On such occasions, Churchill would often contact Beaverbrook to make his feeling plainly known. After one such complaint, Beaverbrook wrote to Sir Samuel Hoare stating that:

'Winston is not on good terms with me at present. He is very sulky about a caricature in the Evening Standard. 'Rival Foundlings'. He spoke to me on the telephone last night for the first time since the affront.'

Apart from attacks on Randolph, Churchill enjoyed Low's sharp wit, even though his cartoons may have at times hurt him deeply: 'I owe him no grudge. Tout comprendre c'est tout pardonner'. One such cartoon was 'On Tour' which was published on 29th January 1935. Seeing it in the Evening Standard that day, Churchill wrote to his wife Clementine stating that:

'I send you a number of cartoons, one a Low cartoon, most amusing, which should make you laugh.'

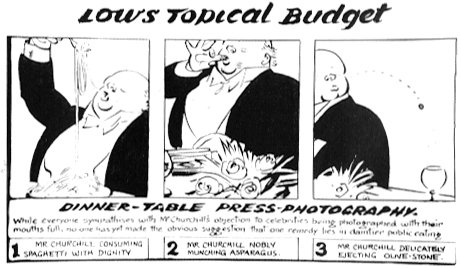

This was an extraordinary response to a cartoon that ridiculed Churchill's opposition to Indian self-government, which by 1935 seemed to be in its last desperate throes. On another occasion, Churchill had written a letter to The Times attacking the intrusion of 'candid camera' fiends who were taking unflattering close-ups of celebrities and politicians such as himself. Churchill's anger brought an immediate response from Low. In his 'Topical Budget', a full-page cartoon which appeared every Saturday, he drew three caricatures portraying Churchill's own eating habits as he mischievously saw them. One would have expected a furious response from Churchill. Instead, he requested the cartoon which when received was carefully framed with his published letter cut out and stuck on the back of the frame.

occasion, Churchill had written a letter to The Times attacking the intrusion of 'candid camera' fiends who were taking unflattering close-ups of celebrities and politicians such as himself. Churchill's anger brought an immediate response from Low. In his 'Topical Budget', a full-page cartoon which appeared every Saturday, he drew three caricatures portraying Churchill's own eating habits as he mischievously saw them. One would have expected a furious response from Churchill. Instead, he requested the cartoon which when received was carefully framed with his published letter cut out and stuck on the back of the frame.

Churchill, recognising Low as the greatest cartoonist of his generation appreciated the political importance of appearing in his cartoons. Low believed that Churchill, as a result from his earliest political days, studied his own caricatures and endeavoured to live up to them. He specifically recalls Churchill's enthusiasm for self-publicity:

'I always try to find Winston Churchill out in something cartoonable mainly because he is so plump and because he likes it and encourages one. He hangs my most vicious works around the Treasury Office.'

Politicians were therefore aware of the importance in enhancing their image amongst the general public by regularly appearing in the cartoons of the day. Politicians would often go further and encourage the cartoonist to advertise what Low called their 'tags of identity.' Baldwin felt it vital to be seen smoking his pipe, which he believed gave him an affinity with the common man. Other politicians promoted their image even if it was detrimental to their person. For example, Austen Chamberlain in an attempt to emulate his famous father Joseph would wear only a monocle even though he was dreadfully short-sighted. This meant that he could barely recognise people at a distance greater than a few feet. On one occasion while sitting for Low, Chamberlain asked 'Must I wear my monocle? I cannot see to read with it very well...' Such blatant attempts by politicians to portray themselves in such favourable light, explain why Churchill became so keen to promote himself this way using cigars, hats, and of course the V sign. Low explains Churchill's keenness for 'tags of identity':

'Statesmen must advertise. Indeed it is vital to the working of our modern democracy that the persons of political leaders be readily identifiable. Cartoonists and caricaturists have their use in creating or embellishing tags of identity, a fact which is not lost on astute politicians... Winston Churchill, for an obvious instance, deliberately advertised himself in his early political days by wearing a succession of unusual hats, and in later years, by always carrying an outsize cigar, foibles which were eagerly used and improved upon by the cartoonists, with his open encouragement. Since the inspiration of these tags is frequently poetic imagination, political analogy or plain prejudice, they are to be accepted as faithful reflections of truth with as much reserve as one accepts the pictures on seed-packets... The early Churchill wore normal hats when the photographers were not around; and in his later years it was noticeable to keen eyes that his public cigars were smoked never more than about one inch.'

As Churchill appreciated, it was the cartoonist's portrayal of him that lodged in the public mind. Low was even bold enough to claim that Churchill's image as war leader was in some way created by the cartoonists: 'Don't imagine', Low said, 'that the familiar wartime idea of Churchill with his V sign and cigar was all his own invention'.

Politicians have always been delighted in finding themselves caricatured in the cartoons of daily newspapers however foolish they may appear. Losing the cartoonists' attention was often the consequence of their fall from the political spotlight. Churchill himself noted that:

'Just as eels are supposed to get used to skinning, so politicians get used to being caricatured. In fact, by a strange trait in human nature they even get to like it. If we must confess it, they are quite offended and downcast when the cartoons stop. They wonder what has gone wrong, they wonder what they have done amiss. They fear old age and obsolescence are creeping upon them. They murmur: "We are not mauled and maltreated as we used to be." The great days are ended.'

The nadir in Churchill's political career can therefore be simply pinpointed by noting his lack of appearances in Low's cartoons for much of the 1930s except over his opposition to Indian self-rule. Churchill's appearances did not even increase when he became one of the few opponents of Chamberlain's policy of appeasing the dictators. Now in his middle sixties, Churchill had become alienated from the Tory leadership, distrusted by both the Liberals and Labour, and appeared to be at the end of his parliamentary life. He was perceived as politically passé, a 'Busted Flush' as Beaverbrook referred to him at the time. Consequently, his warnings over Hitler were not seen as significant even by a sympathetic Low. It was Eden and not Churchill that the country saw as the focus for opposition to Appeasement. According to Low:

'There had never been any doubt about the uncompromising and consistent attitude of Churchill and Eden. But up came that question of loyalty to Chamberlain. Churchill lacking Eden's tact, had become Tory Hate No 1.'

Churchill's years in the political wilderness began with his resignation from Baldwin's shadow cabinet in January 1931. This was as a result of his refusal to accept Baldwin's support for the Labour Government's plans for Indian self-rule. His hostility to Baldwin and the National Government over this issue was to be seen as futile and inevitably detrimental to his chances of ever becoming leader of the Tory Party. Without support in Parliament, or the country, apart from a few Tory die-hards, Churchill was the only prominent politician to lead the opposition to Indian self-government. Alienated from the Tory leadership, many came to think that Churchill's real aim was not the preservation of British rule in India, but an issue on which he could overthrow Baldwin as the leader of the Tory Party. Low's sympathies were obvious, to him there seemed little sense in delaying the legitimate claims of Indians to the right of self-determination. Low saw such a damaging and foolhardy crusade as the efforts of an old fashioned imperialist. For five years, he mercilessly made fun of Churchill's opposition to Indian self-rule, as Low recalls:

'The affairs of India came into my cartoons a lot in the late nineteen-twenties and early 'thirties. The personalities engaged tempted attention on their picturesqueness alone and Churchill supplied enough vehement opposition to the idea of Indian self-government to invite pertinent comment. To the harsh wranglings which brought the break between Baldwin and Churchill I contributed a string of cartoons which directly and indirectly, by ridiculing their die-hard opponents, supported Baldwin and Hoare and their Government of India Bill. As a result I came in for some of the anger flying about. Churchill wrote me off (in his book Thoughts and Adventures, 1932) as a 'green-eyed young Antipodean radical... particularly mischievous... Low's pencil is not only not servile. It is essentially mutinous. You cannot bridle the wild ass of the desert, still less prohibit its natural hee-haw.'According to Churchill I delighted to 'gibe at the British Empire' and was 'all for retreat in India' - which was pretty rich, since by birth, growth and viewpoint I was considerably more representative of the Empire than he was, and probably more advanced too, so far as India and the Commonwealth were concerned.'

Having broken with the Tory leadership over India, Churchill found himself exiled to the back-benches. There he found that without the responsibility of government office, the time to exploit his vast and somewhat neglected literary skills. Apart from writing a voluminous biography of his ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, he found time to contribute a regular article to the Evening Standard every fortnight that mainly concentrated on foreign affairs. Churchill and Low now became colleagues on the same newspaper, which later had the effect of intensifying their mutual opposition to Appeasement in the Evening Standard.

At first, Churchill's views on the European dictators were diametrically opposed to those of Low's cartoons. While Churchill often sang the praises of Hitler and Mussolini as saviours of their respective countries, Low constantly ridiculed both men to the extent that the Evening Standard was banned in both Italy and Germany. As the 1930s proceeded, Churchill woke up to the realisation that Hitler posed a very real threat to peace in Europe, and in 1938 he attempted to rally public and political support for Czechoslovakia. His call for collective action in order to deter German aggression was now very much in tune with the sentiments of Low's own cartoons. However, such views were being actively opposed by their proprietor, Lord Beaverbrook, whose determined optimism over Chamberlain's ability to maintain peace in Europe became too extreme to allow the continued employment of Churchill. His contract was as a result terminated and the Evening Standard Editor R.J. Thompson was given the job of explaining why he had been dismissed. Thompson wrote;

'... your views on foreign affairs and the part which this country should play are entirely opposed to those held by us.'

Churchill indignantly wrote back noting that while he had been sacked, Low was still gainfully employed by the Evening Standard:

'With regard to the divergence from Lord Beaverbrook's policy, that of course has been obvious from the beginning, but it clearly appears to me to be less marked than in the case of the Low cartoons. I rather thought that Lord Beaverbrook prided himself upon forming a platform in the Evening Standard for various opinions including of course his own.'

Thus Low remained, as he was still far too popular amongst the Evening Standard readership even though his cartoons differed little in opinion to Churchill's articles. Such an event could have done little to further endear Low to Churchill, even though the two men were closer in their beliefs on foreign affairs than at any time in the past. In fact, Low's cartoons were becoming so effective in deriding Nazi aspirations that even the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, under pressure from the German Foreign Office, found himself denouncing the Evening Standard cartoonist. According to Low:

'So far as I was concerned Mr. Chamberlain himself set the example. Addressing the Newspaper Society's annual dinner he said that 'German Nazis have been particularly annoyed by criticisms in the British Press and especially by cartoons. The bitter cartoons of Low in the Evening Standard have been a frequent source of complaint.'

Low now found himself labelled along with Churchill as an irresponsible warmonger:

'Abuse grew hysterical. People I knew turned away and wouldn't talk to me. Complete strangers held me up in public places and would talk to me. My tobacconist refused to serve me.'

As both Low and Churchill confidently predicted, Chamberlain failed in his appeasement of Hitler and had little alternative but to declare war against Germany after its invasion of Poland in September 1939. Low appreciated that it was now important to deride the enemy and not the Government in order to boost British morale. However, it appeared that the country was totally unprepared for war and, worse still, Chamberlain seemed to lack any sense of urgency in rectifying the position. To Low this was unacceptable. Only Churchill appeared to have the energy and the appetite for the battle ahead, as his appearances in Low's Topical Budget and cartoons at the time confirm. When Britain's position deteriorated after the Fall of France in June 1940, and the resulting evacuation from Dunkirk, Low knew that Churchill, having replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister, had an uphill - almost impossible; struggle in lifting the morale of the British people. Although having drawn such cartoons as 'All behind you Winston' and 'We have gone too far Adolph' Low was not personally as confident as his morale boosting cartoons suggested. Like Churchill, he knew that he was high on the Nazi death list, and should a German invasion of Britain take place, his chances of survival were minimal:

'But for all the Churchill assurances at the microphone that this was Britain's 'finest hour'; and despite the firm resolve in my suburb (and there were many indications that it was representative) that the invaders would meet a desperate defence by the whole population with any weapons handy, it would have been over-romantic not to recognise that the chances were against us.'

The continued lack of any military success meant that Low carried on ridiculing. His target was not so much Churchill's leadership, but his Government's failure to fight back effectively. This led Churchill to complain consistently to Beaverbrook, who was now in the War Cabinet as Minister for Aircraft Production, about the damage Low's cartoons were doing to the credibility of his Coalition Government. Beaverbrook later referring to this difficult period recalled:

'I had two artists on my hands. One at night-time - that was the Prime Minister complaining about Low. The other in the morning - that was Low complaining about Churchill.'

On one such occasion in December 1940, Churchill was furious about a Low cartoon that had made fun of Arthur Greenwood, the then Labour Cabinet Minister without Portfolio. In a letter to Beaverbrook, in what appeared to be something of an overreaction, Churchill wrote:

'The cartoon in today's Evening Standard against Greenwood will certainly make your path and mine more stony. I know the difficulty with Low, but others do not, and cartoons in your papers showing your colleagues in ridiculous guise will cause fierce resentment.'

In fact, Arthur Greenwood found little offence in the cartoon: "I have no personal feeling against Low." Churchill, however, still continued to remonstrate with Beaverbrook in his belief that such attacks would cause:

'all those ministers conceiving themselves threatened to bank up against you and your projects, and owing to my friendship with you they will think that I am condoning the attacks made upon them. He does you and your work disservice by these cartoons, and he is too well aware of what he does.'

On such occasions Beaverbrook always denied control over Low, stating that it was:

'a matter of real grief" that he should be the occasion of such attacks upon 'my Prime Minister. I do not know how to deal with the situation. I do not agree with Low. I have rarely done so. I do not interfere with Low. I have never done so.'

At this time of great tension, Churchill is believed to have also told Beaverbrook that Low was a: 'Communist of the Trotsky variety'. Although Low's political beliefs were undoubtedly left-wing, to insinuate that he was a Communist subversive was typical of Churchill's own train of thought on this matter. Throughout his political career he always found it difficult to differentiate between British Socialism and Soviet Communism.

So sensitive did Beaverbrook become over Churchill's complaints over Low, that an amusing episode occurred when he spoke on the telephone at cross purposes with the Prime Minister, which as a result nearly ended with the sacking of Stalin. One morning, in the earlier editions of the Evening Standard, there had appeared a Low cartoon which had been highly unpopular with Churchill. Beaverbrook was nervous and guiltily felt some responsibility. Unknown to him, Churchill had since received a particularly insulting cable from Stalin. He later that same day phoned Beaverbrook, and David Farrar, who by accident happened to listen in, heard the following conversation:

Churchill: (in rich post-prandial voice): Max, that fellow Uncle Joe -

Beaverbrook: (On tenterhooks and mishearing): Don't worry, Prime Minister, don't worry.

Churchill: What are we going to do about him? He's sent me -

Beaverbrook (interrupting): Don't worry. I'll sack him tomorrow morning.

Churchill: What are you saying?

Beaverbrook: I'll sack him. He shall never appear in my newspapers again.

Churchill: What are you talking about? I said Uncle Joe.

Beaverbrook: (after a pregnant pause) Oh!

By 1942, Churchill had become increasingly mistrustful of newspaper cartoonists whom he felt were unjustly critical of his Government's running of the war. Philip Zec was severely reprimanded for a cartoon published in the Daily Mirror on 6th March 1942 which Churchill saw as a direct attack on his Government. In fact he had completely failed to grasp the cartoon's message. In a subsequent attack on the press, which was specifically aimed at left wing cartoonists such as Low and Zec, Churchill declared that 'our affairs are not conducted entirely by simpletons and dunderheads as the comic papers try to depict'.

Low, not one to miss an opportunity to hit back at such a comment, replied in the New York Herald that 'for the successful performance of his duties as Nuisance, Low had had to invent a wide variety of imaginary characters to use in his cartoons. Among the most notable of his creations was Winston Churchill and Lord Beaverbrook, who were freely imitated at the time of their appearance by persons claiming to be the originals'.

In 1934, Low had created a reactionary character for his full page 'Topical Budget' that appeared every Saturday. His name was Colonel Blimp, a symbol for stupidity and reaction in British society. Blimp quickly became synonymous with Churchill's attitude towards India. Many believed Blimp had actually been inspired by Churchill, who later became extremely defensive over the character. John Charmley in his recent biography of Churchill, The End of Glory, even entitled a chapter dealing with Churchill's opposition to Indian self-rule as the 'The last stand of Colonel Blimp'. So when in 1942, the British film directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger decided to produce a film based on Low's Colonel Blimp, Churchill naturally became apprehensive over such a project. Since British forces had failed to bring a single victory that could turn the course of the war in their favour, it was generally believed that Blimpishness was alive and well amongst the British high command, and thus detrimental to the war effort. The film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, was therefore going to focus on the limitations Britain faced in fighting a modern war with out-dated methods associated with Colonel Blimp. Churchill not only saw the project as a personal slight upon himself and his leadership, but also as an attack on the morale of the British Army's officer corps. Seeing the film as propaganda in support of the enemy, he did his utmost to have the film banned. Churchill minuted Brendan Bracken at the Ministry of Information:

'Pray propose to me measures to stop this foolish production before it gets any further. I am not prepared to allow propaganda detrimental to the morale of the Army...'

Government financial assistance, which was generally available to the film industry, was as a result refused, and it was made clear that an export licence would not be granted. Although Churchill succeeded in obstructing the export of the film until August 1943, the film became a box office hit, mainly because of his continued efforts in attempting to ban it. A frustrated Brendan Bracken wrote to him emphasising how the Government had inadvertently helped to boost ticket sales for the film:

'As a result of our illegal ban on this wretched film 'Colonel Blimp' has received a wonderful advertisement from the Government. It is now enjoying an extensive run in the suburbs and in all sorts of places there are notices - 'See the banned film!' If we had left that dull film alone it would probably have proved an unprofitable undertaking, but by the time the Government have finished with it there is no knowledge what profits it will have earned.'

For all the Government's anxieties, the suspected focus that Blimpishness was alive and well in British high command was all rather muted. Roger Livesey's splendid but sentimental portrayal of Major General Clive Wynne Candy VC did in no way represent the 'upper class bonehead of invincible stupidity' of Low's own Colonel, while the film's real controversy lay in Anton Walbrook's performance as a sympathetic German, a unique happening in wartime cinema. So why did Churchill, even after attending the film's premiere and seeing for himself that it was all rather harmless, still devote so much time and effort to having the film banned in what was in the midst of a world war? In any event, the war had significantly turned in the Allies' favour by the time the film opened in 1943. Notions of Blimpishness in High Command had also been dispelled by victories in North Africa. Whatever the reasons for Churchill's paranoia and the jumpiness of the government, it does highlight the power of Colonel Blimp's image at the time.

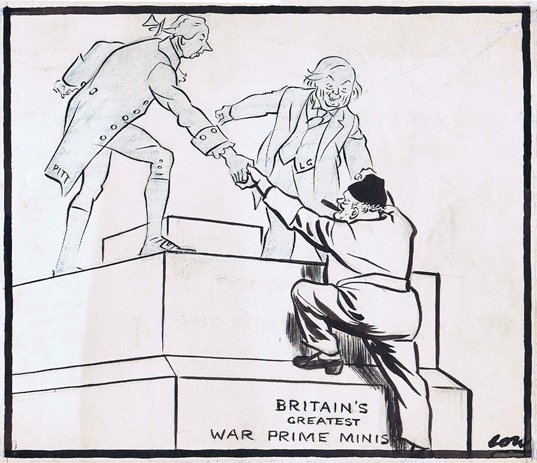

The defeat of Germany led to a peak in Churchill's popularity with the whole country unanimously thanking him for his unique leadership characterised by Low's cartoon of 10th May 1945. Unfortunately for Churchill such a tidal wave of support was personal and did not extend to the Conservative Party. The decision by the Labour Party, to leave the Coalition Government before victory over Japan had been achieved, forced the Prime Minister into becoming for the first time, a party leader rather than a national one. Low had wholeheartedly supported Churchill's leadership throughout the war, but strongly believed that the Conservative Party should be properly judged on its pre-war track record, however great the war-time achievements of its leader. The public was not prepared to risk having the same post-war broken promises that had occurred after the last war in 1918. According to Low:

'The fighting men and their families did not forget the pre-war years of Tory rule, when it came to the 1945 election. They admired Churchill and owed their freedom to him but they remembered the Baldwin-Chamberlain years of Tory rule. They remembered Lloyd George and his land fit for heroes khaki election.'

With a general election imminent, Low mercilessly attacked the attempts both by the Prime Minister and his Party to remain in office, even though his proprietor was in overall charge of the Tory election campaign. Low describes how this affected allegiances during the campaign:

'Beaverbrook and his newspapers had loyally upheld Churchill and the Conservatives and I had consistently supported the Labour Party and ridiculed Churchill's attempt to make the prominent Socialist Professor Laski the bogey of a scare campaign. Not for the first time the Evening Standard and I had been in flat opposition. Yet, as should be in a civilised community, that made no difference to personal relations.'

Low took full advantage of the Tories' rather negative election strategy, especially Churchill's first election broadcast in which he insinuated that the Labour leader Clement Attlee, would, if elected, have to fall back on some form of Gestapo in order to create a Socialist State. When the election results were eventually announced, they were not as expected. There was no victory for the man who had won the war, but instead a landslide victory for the Labour Party. Lord Beaverbrook became the Tory Party's favourite scapegoat, as leading Conservatives blamed him for their disastrous electoral performance. To them his employment of prominent left-wingers, like Low, who had done their damnedest to vilify their Party over the years, had had a cumulative effect on public opinion. Had not the frequent appearances of Colonel Blimp as the archetypal reactionary Tory, proved so damaging to the public's perception of the Conservative Party?

The Labour Party had a majority government for the first time in its history. Although their manifesto had differed little to that of the Tories in substance, it was the public's general consensus that it was Labour, rather than the Tories, that would be more likely to carry out its election promises. Low saw the now despairing Churchill in terms of both hero and anti-hero. In one respect Churchill was still the great war leader, while on the down side he was the failed politician, the man who had frequently misjudged the political climate, and had just led his Party to a humiliating defeat. As Leader of the Opposition, Churchill offered only criticism of Socialism instead of offering an alternative in the way of new Tory policy. With Labour having such a big majority there was little he could achieve in any case for the next five years. Low derided Churchill's refusal during the whole of Labour's term in office to be pinned down on specific policy. Churchill would only repeat that he would wait and see what the economic circumstances were at the time of the next election. According to Low:

'The Conservative Party has not a policy but it has Churchill who has elevated not having a policy into a virtue, scoffs at the Labour men as having one, and once advised his friends to have no ideas at all until the necessity arose. Mr C is universally loved. The general view is that he won the war, and on that account most people would like to clear away the Nelson monument from our best site to make room for a statue of Winston on the top of a 500 foot high stone cigar.'

Consequently, Low created Micawber Churchill who made his first appearance in February 1947(183), pronouncing that he was 'waiting for something to turn up'. Had Low gone too far this time? There was immediate uproar amongst Evening Standard readers, who filled the letters pages denouncing Low's ridicule of such a great man. Naturally they demanded Low's head. Under pressure the Editor announced: 'What shall we do with Low?' 'Send him back to New Zealand!' was the response from one retired ex-Admiral.

In Churchill's desperate attempt to regain office, Low began to exploit the contradictory nature of his recent acceptance of the Welfare State and his promise to accept the bulk of the Labour Government's legislation. Churchill had become, to Low, not so much the leader of the Conservative Party but of himself:

'Churchill had stolen his new programme from the Labour clothesline. Nationalisation yes, controls, rationing priorities, state trading, Labour like planning, Tories were to do it with tears in their eyes.'

Churchill, happy to allow his own Party to be dominated by those on the left, found that by the 1950 General Election, Conservative policy differed little to that of Labour. Although the Tories lost once again, a very tired Labour Government had its large overall majority reduced to only five seats, and as a result survived only for a further year, with Churchill finally winning the 1951 General Election. His second term in office, as Low illustrated, was dominated by his preoccupation with foreign affairs. This culminated in his wish to bow out of politics after having secured, and participated in, a summit between East and West in order to reduce the continued threat of nuclear war. Hence, few of Low's cartoons during this period relate to Churchill's concerns over Britain's domestic problems on economic or social issues. Low also captured the inherent frustrations of Anthony Eden, Churchill's heir apparent, and other Cabinet Ministers who felt he was becoming more and more of a liability the longer he remained in office. Churchill had originally let it be known that he would retire soon after becoming Prime Minister again, but having once more tasted high office, he successfully delayed any plans for his retirement for a further four years.

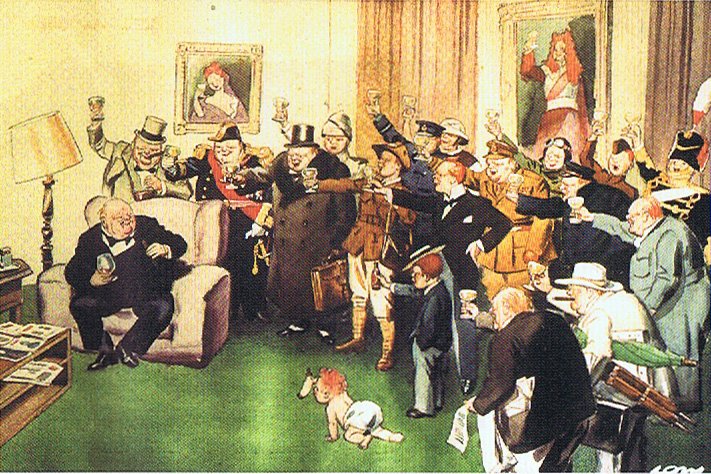

Low by now at the Guardian, was also winding down after a long and remarkable career. His cartoons were no longer the great works of draughtmanship they once were, but his astute understanding of politics and his ability to satirise were still at times as good as ever. He had by now been caricaturing Churchill for nearly 40 years and was beginning to admit that he 'had exhausted the possibilities of Churchill and there was no longer pleasure in drawing him'. But his affection and respect for the old man as he approached his 80th birthday kept bursting through. Commissioned by the London Illustrated News to draw a commemorative cartoon for an eightieth birthday edition, Low painted in colour a cartoon featuring a room packed with Winston Churchills, all at different stages of his long and eventful life. Signed 'from your old castigator', London Illustrated News presented the original cartoon to Sir Winston who was delighted with it, unlike his official present, the Graham Sutherland portrait, which his wife later destroyed.

Low by now at the Guardian, was also winding down after a long and remarkable career. His cartoons were no longer the great works of draughtmanship they once were, but his astute understanding of politics and his ability to satirise were still at times as good as ever. He had by now been caricaturing Churchill for nearly 40 years and was beginning to admit that he 'had exhausted the possibilities of Churchill and there was no longer pleasure in drawing him'. But his affection and respect for the old man as he approached his 80th birthday kept bursting through. Commissioned by the London Illustrated News to draw a commemorative cartoon for an eightieth birthday edition, Low painted in colour a cartoon featuring a room packed with Winston Churchills, all at different stages of his long and eventful life. Signed 'from your old castigator', London Illustrated News presented the original cartoon to Sir Winston who was delighted with it, unlike his official present, the Graham Sutherland portrait, which his wife later destroyed.

As the years took their toll, Churchill became subjected to attack from those who wished to portray him as senile and ineffectual. It had never been in Low's style to extenuate the signs of physical or mental decline in any of his subjects. Although appearing somewhat bedraggled, Low's elderly Churchill always had a dynamic energy even during the bleak years of his retirement. Unlike Low, Malcolm Muggeridge was one of the first to underline Churchill's faltering abilities when he allowed Leslie Illingworth to produce a cruel cartoon for Punch which depicted an incapacitated Prime Minister. Churchill was bitterly hurt by the cartoon: 'Yes, there's malice in it. Punch goes everywhere. I shall have to retire if this sort of thing goes on.' While in contrast, Low's last cartoon of Churchill 'Battle of Middlesex Hospital' typified the spirit in which he had always drawn him. Here we see an ailing 88-year-old Sir Winston hospitalised but nevertheless still indomitably battling on against all comers (Field Marshal Montgomery in this instance). By the time that Low and Churchill had died, in 1963 and 1965 respectively, both had left their own indelible impression on 20th Century. One can be considered its greatest cartoonist and the other its greatest statesmen.

View Account

View Account